The Late 17th Century

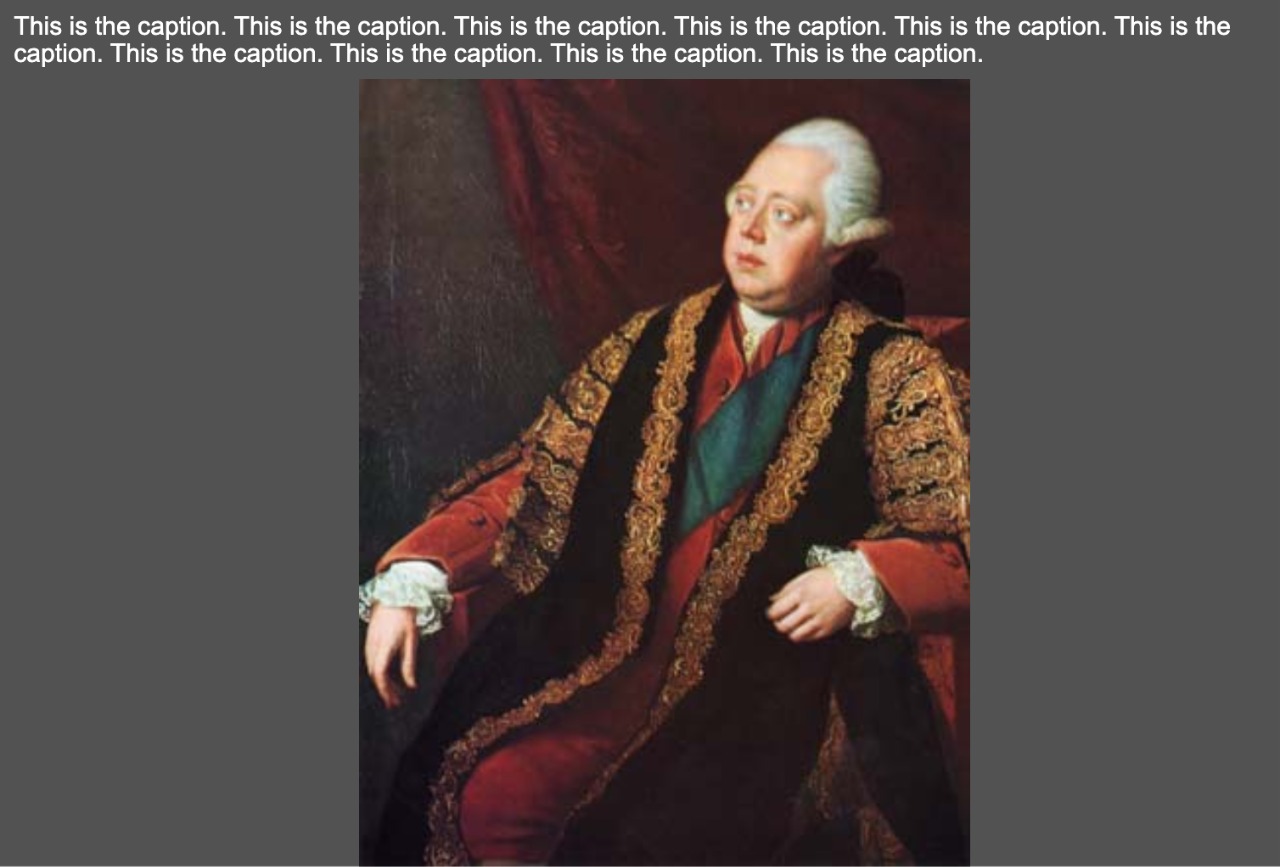

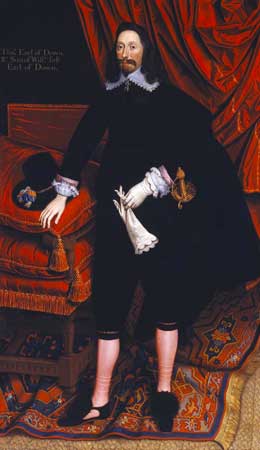

Francis North, Lord Guilford

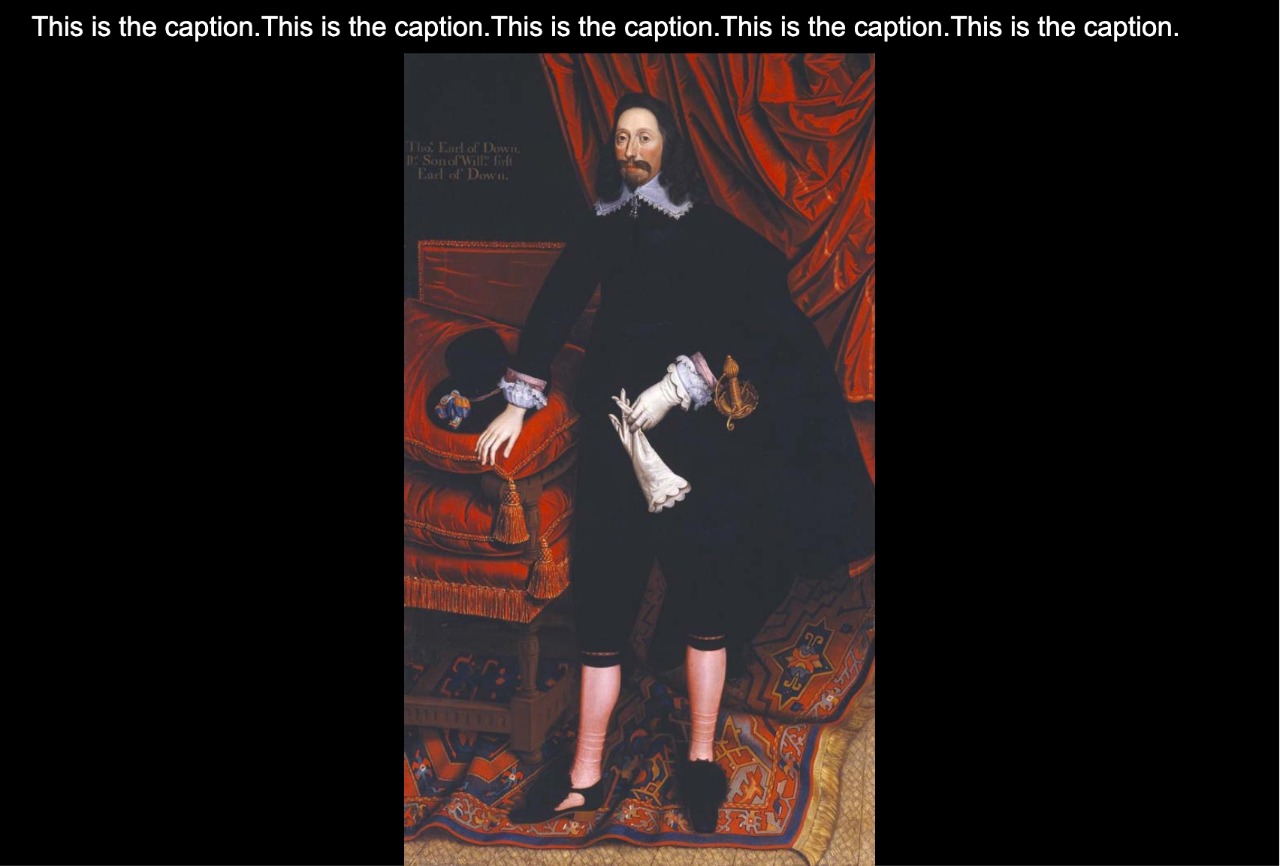

The 3rd Earl of Downe’s only son inherited the title and properties when his father died in 1667. But a year later he also died, bringing an end to the Earldom. The Wroxton lease was inherited by his three sisters and their cousin, Lady Elizabeth Lee.

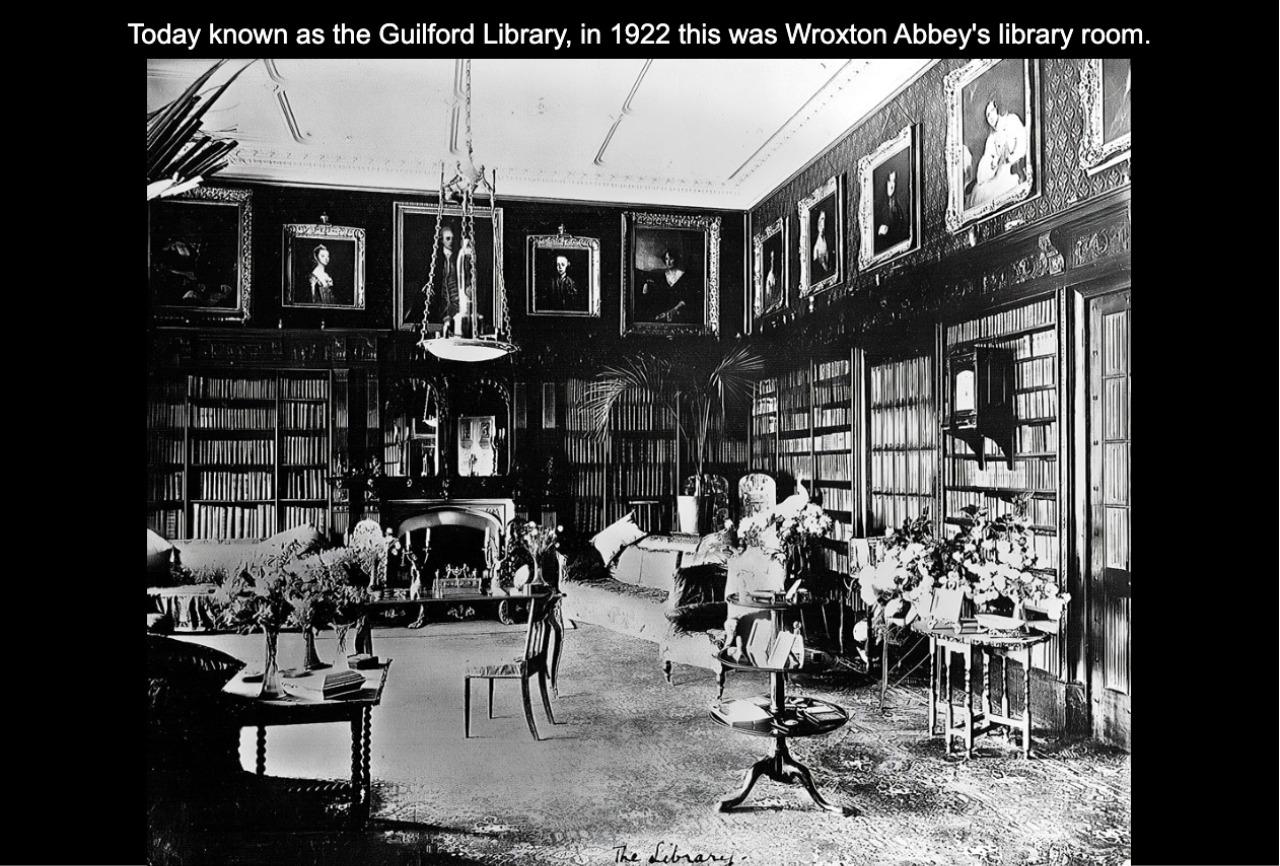

One of the sisters, Lady Frances Pope, married Francis North in 1672. In 1681, following the death of the third Earl’s widow, Sir Francis North, now Lord Guilford and Chief Justice of Common Pleas, bought out the inheritance of his sisters-in-law and their cousin for £5,100. The Wroxton lease was now North property and remained so for 250 years. Lord Guilford was to spend much of his leisure time at the Abbey with his two brothers and his sisters, a company he labeled societas exoptata. According to his brother Roger North, Lord Guilford made Wroxton:

“…his Retirement for vacations, the place afforded him very much pleasure, for he took his nearest relations and friends downe with him, and ever kept his family full.”

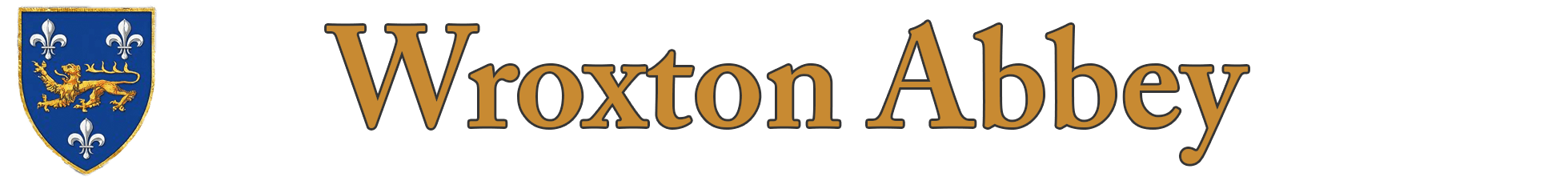

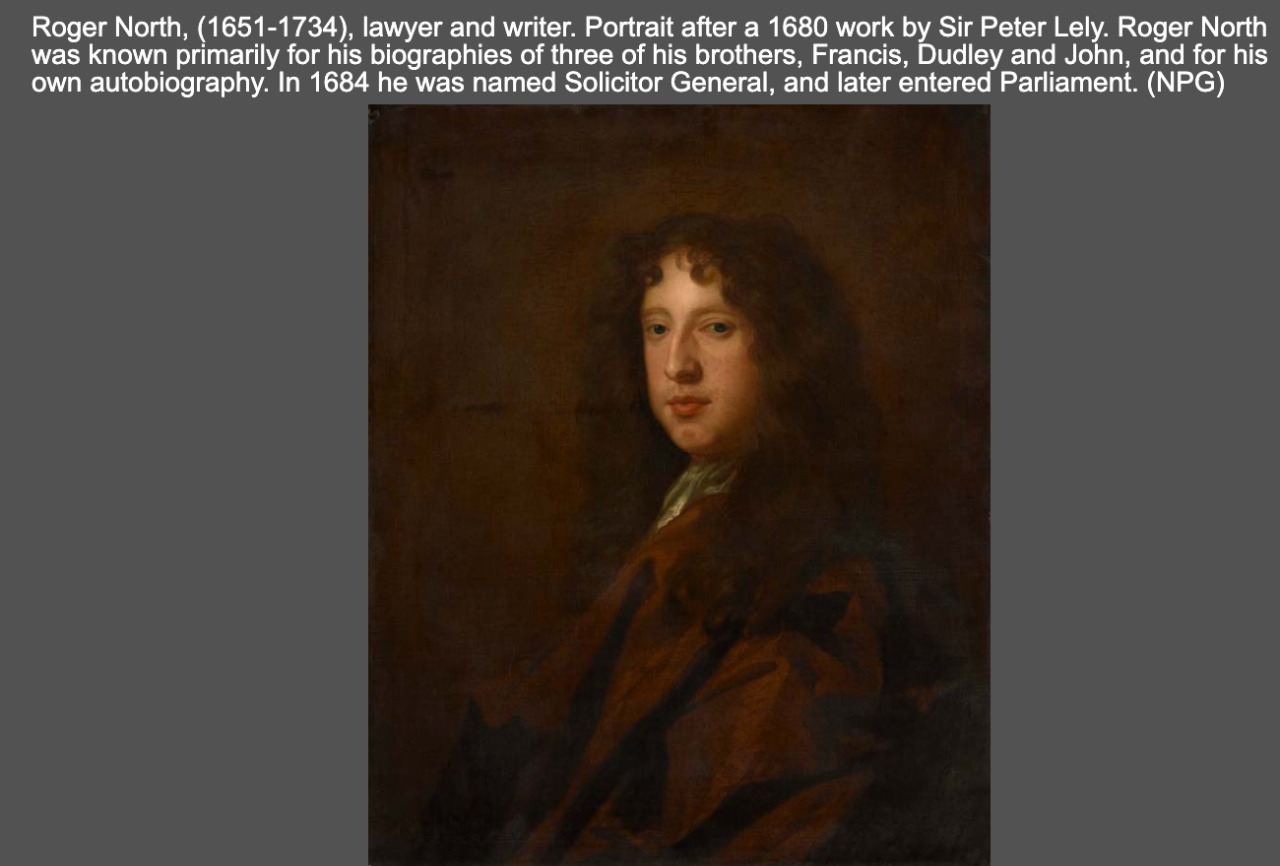

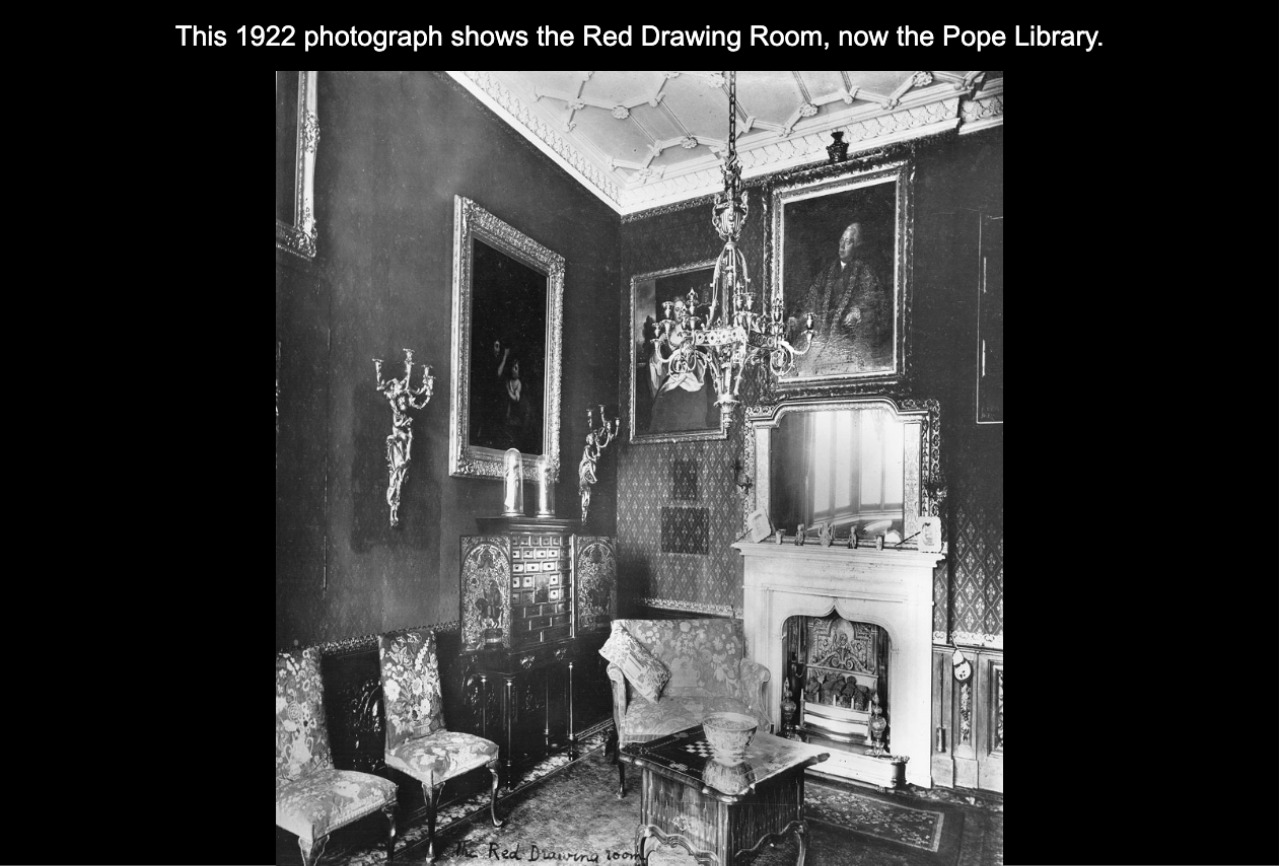

Roger North described the alterations to the main house as building from the ground a withdrawing room and back stairs and finished up the rooms of state, as they were called, and shaped the windows, which before had made the rooms like bird cages. (Lives of the Norths, 1826).

By 1683 the project was complete apart from some wainscoting in the withdrawing room and great bedchamber When Celia Fiennes visited, she approved of the alterations as “all the new fashion way.” (Through England on a Side Saddle, 1888).

Roger North

During his last illness, Lord Guilford retired to Wroxton, partly due to his affinity for the Abbey and partly due to the recent discovery of the “medicinal properties” of the waters at nearby Astrop. He took the seal with him and carried on his work from the Abbey until he died aged 47 on 5 September 1685, still in office as Lord Chancellor and Lord Keeper of the Great Seal of England.

Before his death he improved the old house by making the north wing habitable and adding stabling. The property was only leased to him, and this may have inhibited greater spending. Together with his brothers, Roger, an accomplished architect, and Dudley, he built “an ordonnance of stabling” south of the house, partly financed by the sale of timber, though still being paid for after his death. He corresponded with his steward Francis White on the design:

“Whereas my first intentions were to have the whole building one entire through stable I think it better to divide the same by walls and to have two doors and also several stables at least…which will be more safe, more private and more convenient.”

(North MSS, Bodleian Library).

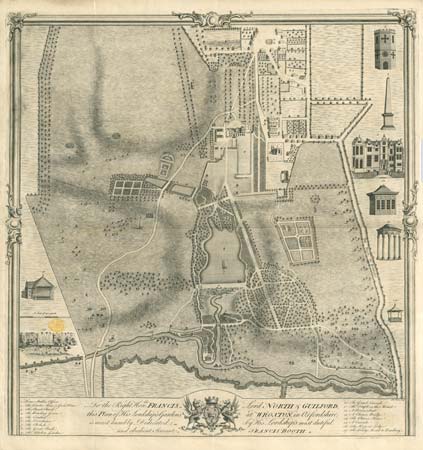

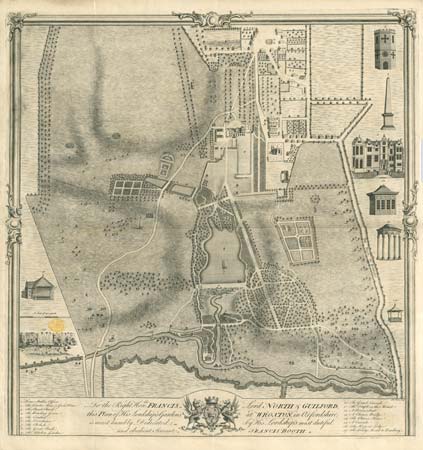

Booth Garden Plan, c. 1750. Click to see in a fully detailed, draggable view.

The building housed coaches, horses, and later provided a brew house and laundry. The latter was destroyed in the early part of the twentieth century and the stabling converted to a lecture hall, dining room and bar with a kitchen in 1974-5 by Geoffrey Forsyth Lawson for Fairleigh Dickinson University.

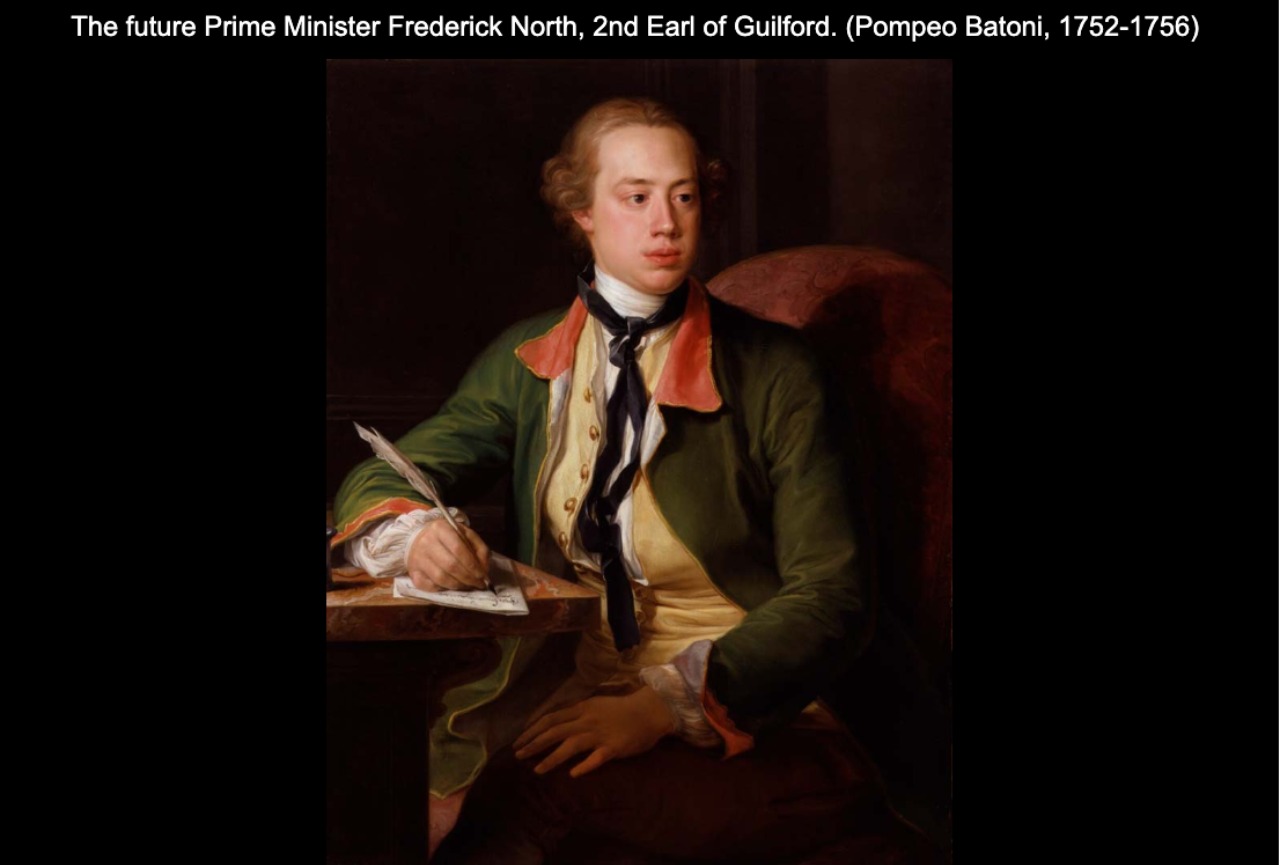

In 1727, Francis, the second Baron Guilford decided that Wroxton should have a garden on a scale that would correspond with the recently much improved house.

Tilleman Bobart, a son of Jacob Bobart, the first curator of the Oxford Botanic Gardens, was commissioned as the designer. Bobart had trained under Henry Wise, the Royal gardener at Hampton Court Palace and at Blenheim Palace, before setting-up on his own.

At Wroxton, he removed the old orchard and constructed two terraces along the slope of the land on the east side of the house. The higher platform was a terrace walk, and the lower terrace contained a central canal, 240 feet long, 40 feet wide and 3-4 feet deep. Bobart also altered the entrance court and carried out works to the parlor garden on the north side of the house.

In 1730 Bobart constructed the walled garden on high ground to the northeast. It is thought likely that Bobart was also responsible for the stone-built icehouse situated on the northern boundary of the grounds.