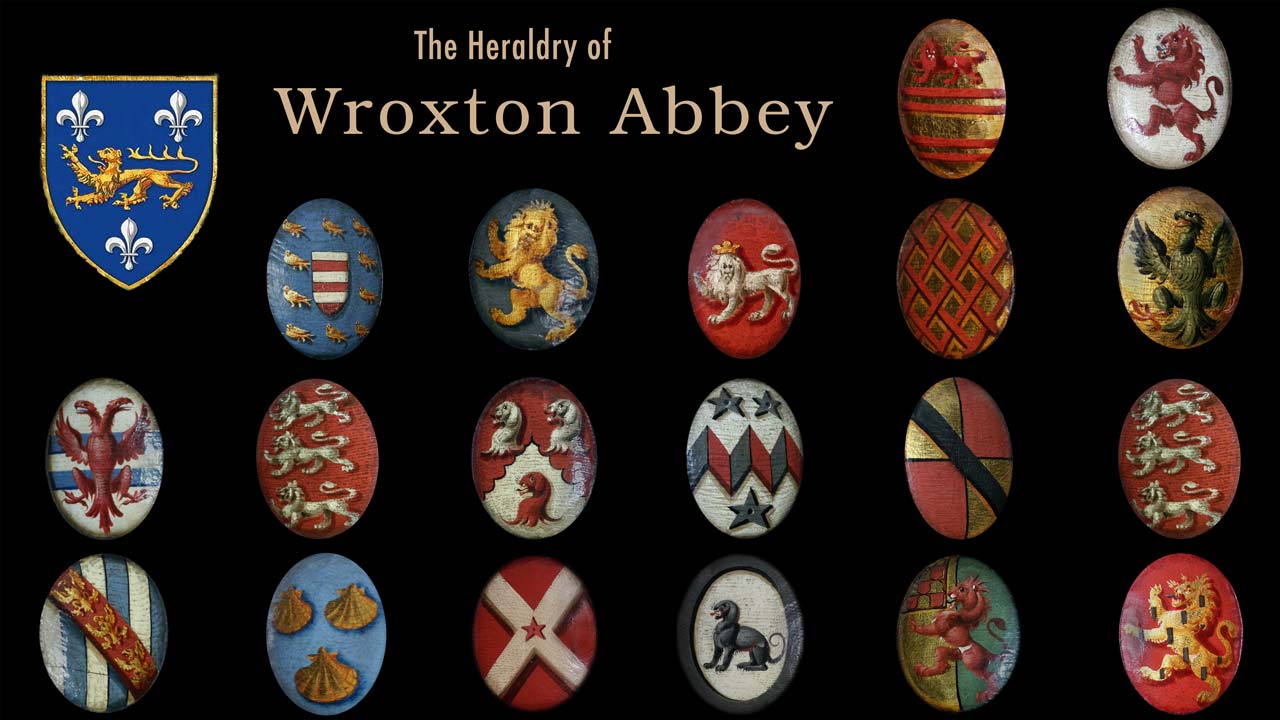

Along the walls of the Great Hall are painted heraldic shields from

the different families associated with Wroxton Abbey.

The Families of

Wroxton Abbey

Along the walls of the Great Hall are painted heraldic shields from

the different families associated with Wroxton Abbey.

Families who have lived at Wroxton: The Popes

By the time the 13th century Augustinian priory at Wroxton was dissolved in 1536 it had decayed to being a “house of small rents” maintained through the good management of the home farm. The property was leased the next year and eventually purchased by Sir Thomas Pope.

Born the son of a minor local landowner, and trained as a lawyer, Sir Thomas had risen to become Treasurer of the Court of Augmentations, the government ministry responsible for the “privatization” of the newly dissolved monasteries. He died in 1559 as one of the richest commoners in England, so it was said, possessing some thirty manors, most of which, like Wroxton, had been monastic property acquired through his privileged position.

Having no children by his three marriages, he left much to churches, prisons, hospitals, and other charities, including Trinity College at Oxford, which he founded in 1555 on the site of yet another of his ex-ecclesiastical acquisitions. All the same, his collateral descendants were still enjoying much of his monastic spoils over three centuries later.

The immediate beneficiary was Sir Thomas’s brother, John, who left the property to his son William. It was William who began the present-day building: a lesser prodigy house to match his rise into the ranks of the lesser Irish aristocracy with his hard bought, but obscure, titles of Baron Belturbet and Earl of Downe.

These titles and lands worth £2,200 per annum went to William’s infant grandson, Thomas, but the house and estate at Wroxton remained in the hands of their long-time occupant, Thomas’s uncle, Sir Thomas Pope. The young Thomas, second Earl of Downe, after being sent down from Oxford University, became a rakehell Cavalier who amassed £11,000 worth of debts in the cause of Charles I and his own private pleasure.

Fined a further £5,000 by Parliament for his royalist activity, Thomas was forced to sell almost all of his lands and to live abroad in chastened circumstances until just before his death. His uncle, who had foolishly tried to court both the Cavaliers and the Roundheads, and thus had also suffered in the Civil Wars, had the grace to bury his nephew in Wroxton Church when he inherited the Earldom in 1661. He lived to enjoy his title for six years, but his son survived him for only another one. The title became extinct and Wroxton with its properties was divided between Sir Thomas’s three daughters.

The Norths

One of Sir Thomas Pope’s three daughters, Frances, married the lawyer responsible for the contentious settlement of the Pope estate, Francis North. He was a gifted advocate, making as much as £7,000 a year from his practice, who by his aptitude, his application to the “cocks of the circuit” and his subservience to the royal prerogative of Charles II, rose to become Lord Chancellor and the first Baron Guilford.

In 1681, he bought out the shares in the Wroxton estate held by his deceased wife’s sisters for £5,100. Before his death in 1685 he did much to extend William Pope’s original building. In this he was aided by his youngest brother, Roger, an accomplished architect, barrister, musician, and scientist. Francis’s son, also Francis, inherited the Barony of Guilford and passed it on in turn to his son, yet another Francis, in 1727.

This Francis improved the family status by inheriting the Barony of North from an extinguished senior branch of the Norths and raised its prestige further by his place in the affections of Frederick, Prince of Wales.

The Prince of Wales, while attending the Banbury Races in 1739, stayed at the Abbey. Apparently, he has such a fine time that he requested the visit be commemorated by the erection of a monument.

Although the Prince met an unfortunate end in 1743 after (according to legend) his skull was fractured by a tennis ball, his obelisk stands today on the center of the former estate’s farmlands above the lakes.

Later, Wroxton would receive other royal visitors: George IV (as Regent) in 1805, and the Duke of Clarence (later William IV) in 1806. The drawing room was redecorated for the Prince Regent, and later named the Regency Room.

Francis was raised to the Earldom of Guilford in 1752. His son, named Frederick in honor of the royal association, better known by his courtesy title of Lord North, is perhaps the most well-known of all the Norths.

Frederick Lord North

Born 13 April 1732, died 5 August 1792 – resident of Wroxton Abbey, Knight of the Garter, sometime constable of Dover Castle, Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, Chancellor of Oxford University, Chancellor of the Exchequer and Leader of the House of Commons between 1767 and 1770. Frederick Lord North served as “Prime Minister,” a title he abhorred, for twelve years between 1770 and 1782.

In his Memoirs, Horace Walpole provides a portrait of Lord North in 1770:

“Nothing could be more coarse or clumsy or ungracious than his outside. Two large prominent eyes that rolled about to no purpose (for he was utterly short-sighted), a wide mouth, thick lips, and an inflated visage, gave him the air of a blind trumpeter. A deep, untuneable voice, which, instead of modulating he enforced with unnecessary pomp; a total neglect of his person, and ignorance of every civil attention, disgusted all who judge by appearance, or withhold their approbation till it is courted. But within that rude casket were enclosed many useful talents . . .”

“Nothing could be more coarse or clumsy or ungracious than his outside. Two large prominent eyes that rolled about to no purpose (for he was utterly short-sighted), a wide mouth, thick lips, and an inflated visage, gave him the air of a blind trumpeter. A deep, untuneable voice, which, instead of modulating he enforced with unnecessary pomp; a total neglect of his person, and ignorance of every civil attention, disgusted all who judge by appearance, or withhold their approbation till it is courted. But within that rude casket were enclosed many useful talents . . .”

Lord North, perhaps more than any other British politician, has been the victim of historical mythology. Popularly dubbed “Britain’s worst Prime Minister” on the grounds that he lost the American colonies, he has also been condemned by generations of historians as a Parliamentary Trojan Horse, namely as a vehicle for a sovereign who threatened the country’s political liberty.

And yet, in the context of his age, he was a master politician who dominated the Parliamentary stage. He had very real achievements in such fields as finance, Ireland, and India, which should not be ignored simply because of the loss of the American colonies. Similarly, whether in office or in opposition, Lord North held consistently to the constitutional doctrine that, in the last resort, power lay in the House of Commons. In one letter, he directly addressed the King on this issue.

Highly popular at Westminster, and a man of unquestioned honesty and integrity, he retained the respect of his contemporaries throughout his career. It fell to Lord North to be contradicted by events, to be disappointed in his hopes. Nonetheless, take away the advantage of hindsight and, if not a great Prime Minister, he was by no means the failure of legend.

Frederick, Lord North outlived his father by only two years and a day, and the earldom was passed in succession to each of his three sons: George Augustus, a Maverick politician; Francis, an army colonel, and West End playwright; and Frederick, a colonial governor and Hellenic scholar.

There being no male heir to any of them, the Earldom of Guilford was passed to a cousin while the Barony of North was devolved, by order of the House of Lords in 1837, upon George Augustus’s lovely daughter Susan. The new Baroness North was such a noted beauty that her image was still being used on popular decorative items a century later. Lady Susan married Lieutenant Colonel John Doyle, M.P. in 1835. To perpetuate the family line, in 1838 her Irish Catholic husband took the name of North.

Their son, William Henry John North, born in 1836, was the eleventh Baron and the last North to live at Wroxton Abbey. After his death in 1932 at the age of 96, the family was unable to bear the great expenses of maintaining the mansion and its staff. The Abbey lease was surrendered to Trinity College in 1932 and its art and furnishings sold at auction.

William Henry’s son, William Frederick, became the 12th Baron North, to be succeeded by his grandson Lieut. John North. He was lost at sea in the H.M.S. Neptune in 1941. Dudley, his father, had previously died in 1936. Thus, the Barony of North fell into abeyance between John’s sisters.

Their son, William Henry John North, born in 1836, was the eleventh Baron and the last North to live at Wroxton Abbey. After his death in 1932 at the age of 96, the family was unable to bear the great expenses of maintaining the mansion and its staff. The Abbey lease was surrendered to Trinity College in 1932 and its art and furnishings sold at auction.

William Henry’s son, William Frederick, became the 12th Baron North, to be succeeded by his grandson Lieut. John North. He was lost at sea in the H.M.S. Neptune in 1941. Dudley, his father, had previously died in 1936. Thus, the Barony of North fell into abeyance between John’s sisters.

For more information on the history of Wroxton Abbey and its families, explore the collection of books at The Wroxton Chronicles.

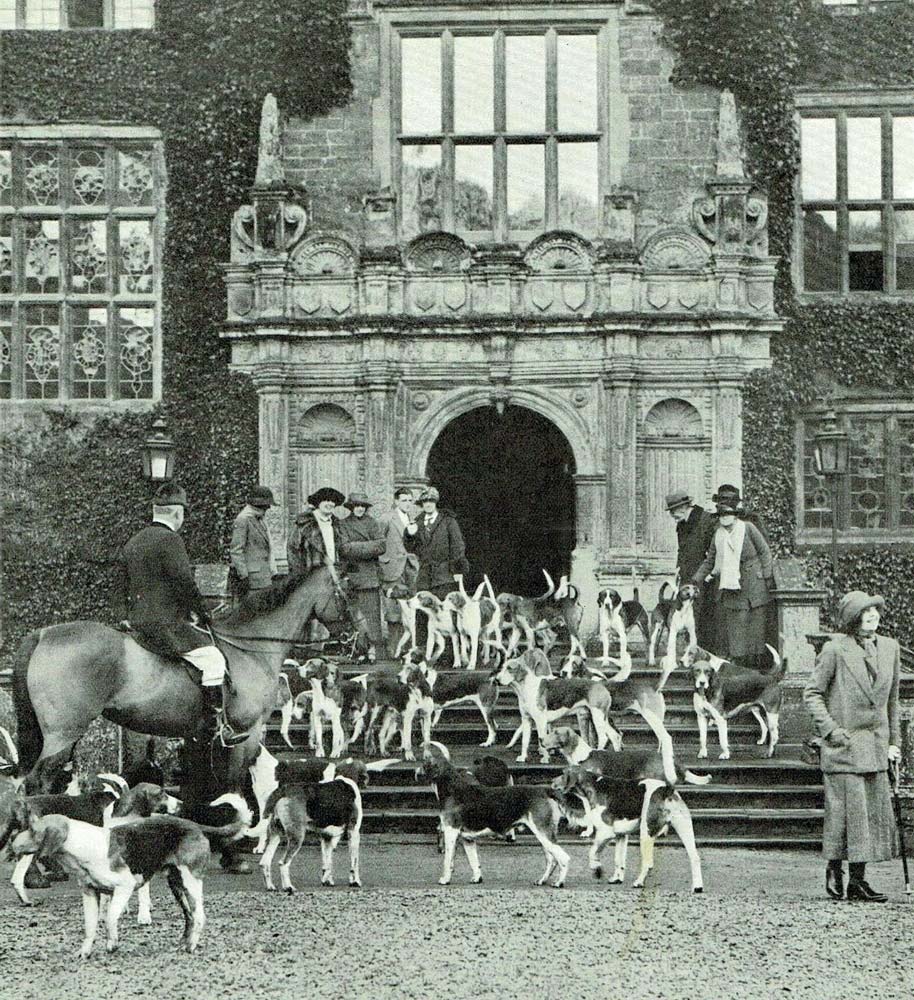

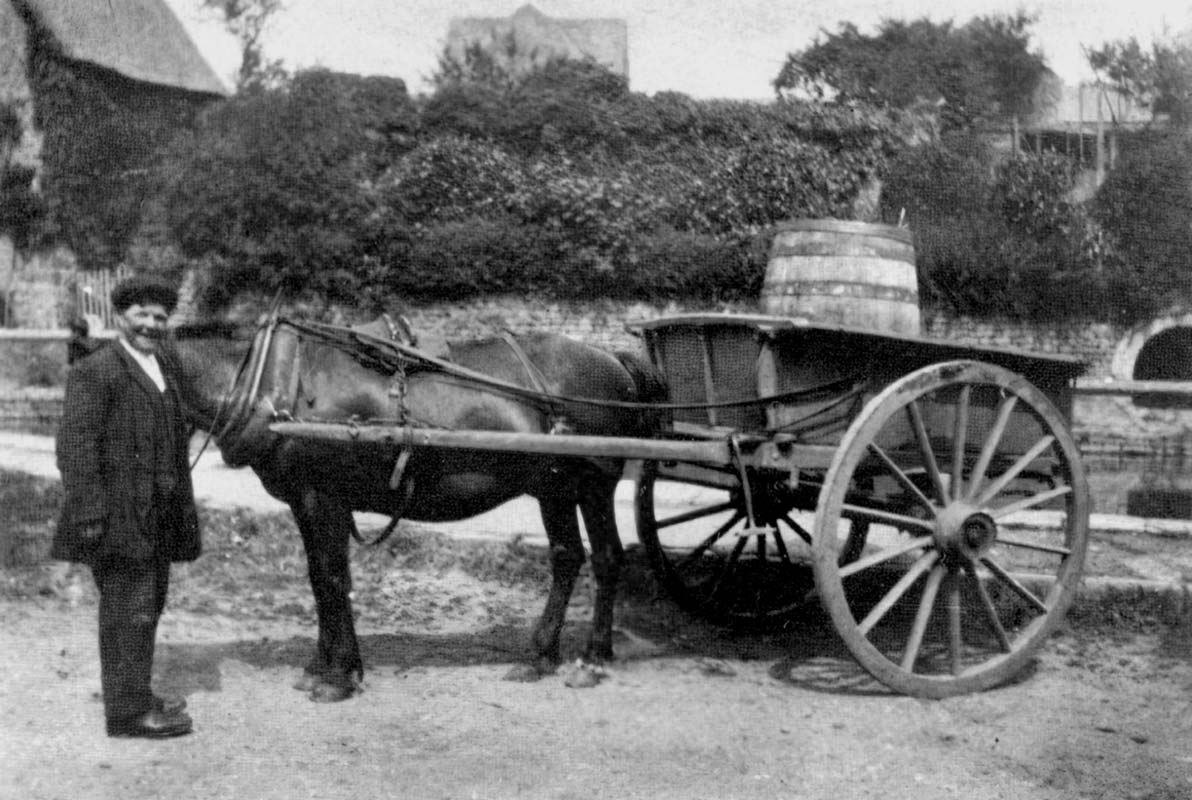

Early 20th Century Wroxton Photo Gallery

Double-click to view full screen.

Early 20th Century

Wroxton Photo Gallery